Walk into your home right now. Open your wardrobe. Check your bathroom cabinet. Count the brands.

You’ll find dozens, maybe hundreds. Shampoo bottles, t-shirts, socks, skincare, underwear.

Now ask yourself: How many of these brands do you actually feel “loyal” to? How many founders could you name? How many brand stories could you recite?

The answer, for most people, is almost none.

We buy these products because they’re available. Because they showed up when we needed something. Because a friend mentioned them, or an ad caught us at the right moment, or the store we walked into happened to stock them.

This is the truth the fashion industry refuses to accept: loyalty is not what you think it is.

After working with hundreds of fashion brands, I’ve watched the same pattern destroy promising companies over and over. Founders obsess over loyalty programs, retention campaigns, and “community building” while their brands slowly bleed out from a much simpler problem: not enough people know they exist.

The data is unambiguous. Research from the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute shows that brands grow primarily through customer acquisition, not retention. Loyalty follows market share, not the other way around.

The Law That Explains Everything

In the 1960s, sociologist William McPhee discovered something strange while studying radio listeners. Less popular radio stations didn’t just have fewer listeners; those listeners also tuned in less frequently than fans of popular stations.

The small stations were getting hit twice.

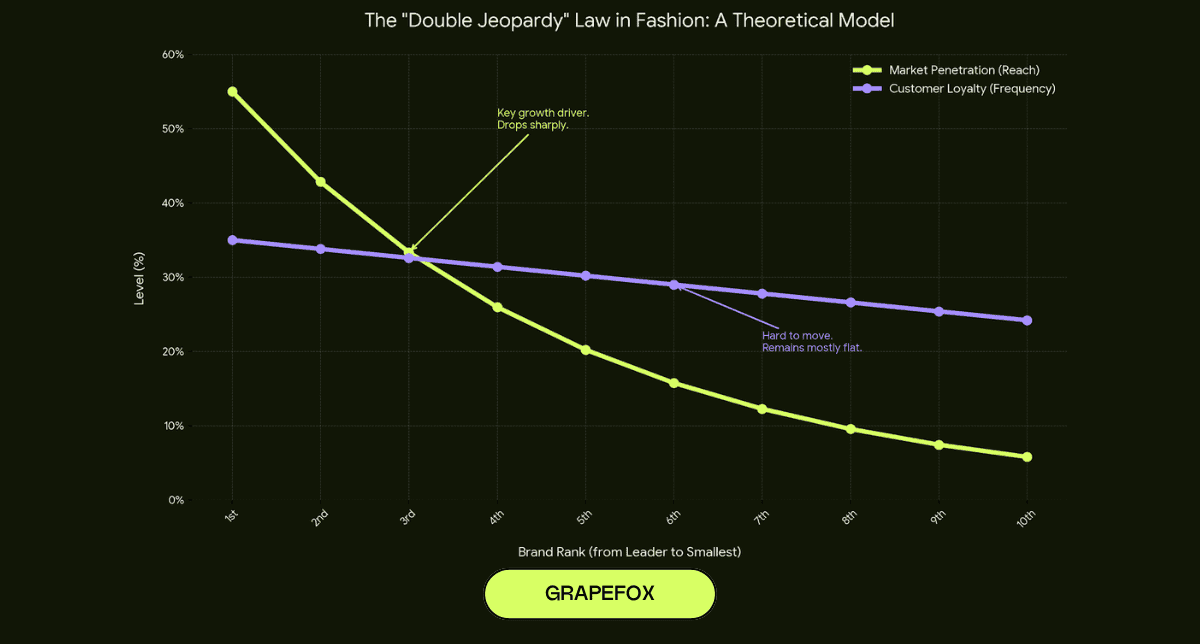

Professor Andrew Ehrenberg later applied this finding to brand purchasing, and what he discovered has since been validated across every product category tested, in every country where data has been collected. He called it the Double Jeopardy Law.

Here’s how it works: Small fashion brands suffer two penalties simultaneously. First, they have fewer customers. Second, those customers buy from them less often.

This isn’t a marketing failure. It’s not because small brands have worse products or weaker “brand love.” It’s an empirical pattern so consistent it appears in shampoo, fashion, automobiles, banking, and streaming services.

The Ehrenberg-Bass Institute (the world’s largest centre for marketing research, with sponsors including Coca-Cola, Mars, Procter & Gamble, and Netflix) has spent 20 years documenting this.

Their data illustrates it clearly: the gap between brands is almost entirely explained by how many people buy them, not by how often those buyers return.

What this means for fashion brands:

Consider two brands competing in the same contemporary womenswear space:

- Brand A (established player): 100,000 customers purchasing an average of 4 times per year = 400,000 annual transactions.

- Brand B (indie brand): 5,000 customers purchasing an average of 3.2 times per year = 16,000 annual transactions.

Brand B isn’t just 20x behind in customer count. It’s 25x behind in total transactions.

Here’s the painful part: Brand B’s founder probably believes their customers are “more loyal” than Brand A’s customers. They point to their engaged Instagram community, their high email open rates, their passionate customer reviews.

But the data shows their customers actually purchase less frequently. That’s Double Jeopardy in action.

The difference in purchase frequency (4.0 vs 3.2) seems small. The difference in customer count (100,000 vs 5,000) is massive. And that’s the whole game.

The Loyalty Program Illusion

According to McKinsey, US companies spend $50 billion a year on loyalty programs alone. Fashion and retail have embraced points systems, VIP tiers, birthday discounts, and exclusive member access as core growth strategies.

But here’s what research reveals: loyalty programs largely reward pre-existing behavior rather than creating new loyalty.

Studies tracking thousands of households across multiple loyalty programs found that when researchers controlled for self-selection bias, the actual behavioral effect of loyalty program membership was significantly smaller than naive analyses suggest.

The programs weren’t creating loyalty. They were identifying customers who were already loyal and giving them discounts they didn’t need to receive.

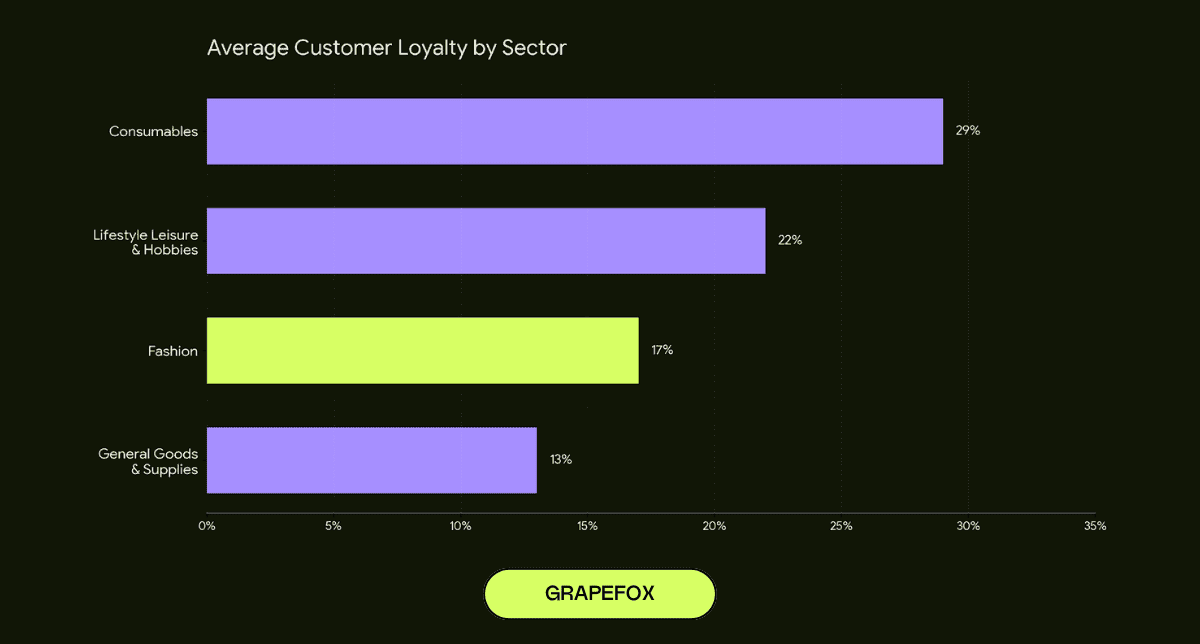

Fashion has particularly low customer retention. According to industry benchmark data, fashion and apparel e-commerce has only a 16% customer loyalty rate (meaning 16% of customers return to make another purchase). This ties for the lowest rate among major retail categories. Compare that to consumables at 29%.

And the engagement statistics across all loyalty programs are sobering: 54% of memberships are inactive. The average consumer holds 19 memberships but only actively uses about half of them.

How the Winners Actually Won

Zara: €36 Billion Through Physical Availability

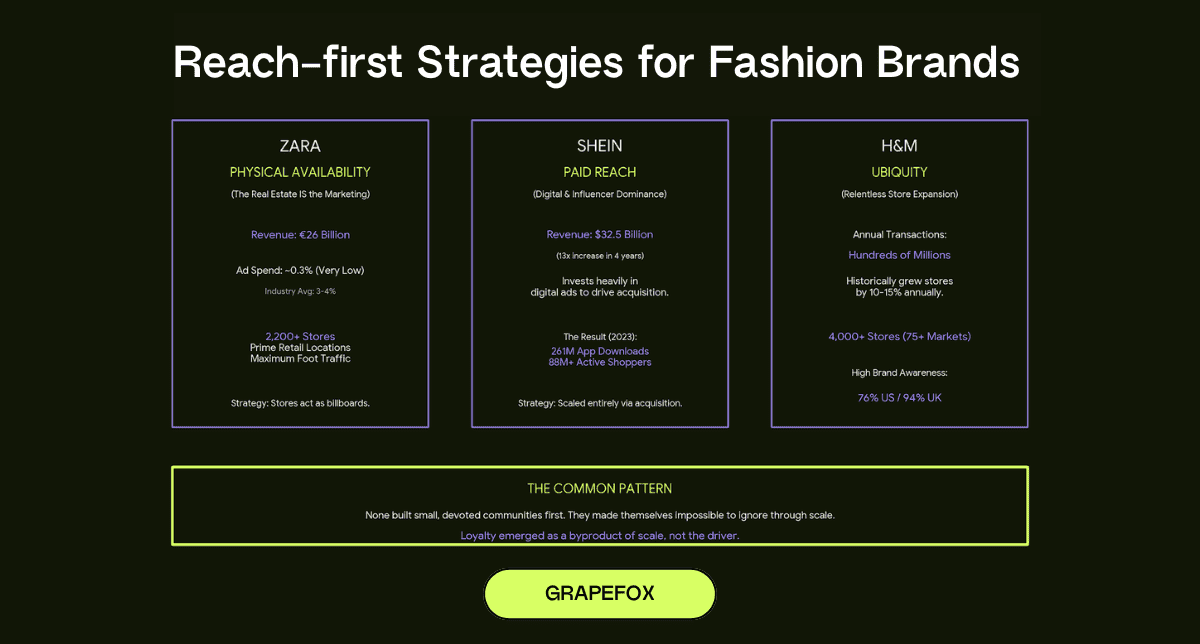

Zara generated €26 billion in revenue in 2023 as Inditex’s flagship brand (Inditex overall generated nearly €36 billion). The company spends approximately 0.3% of its revenue on advertising, compared to the industry average of 3-4%.

That seems to contradict everything about reach. No advertising, yet massive market share?

Look closer. Zara doesn’t buy media reach. It buys physical reach.

The brand operates over 2,200 stores across 93+ markets, concentrated in prime retail locations with maximum foot traffic. Every store functions as a billboard. The real estate IS the marketing.

The strategy is reach-first, just executed through a different channel. Zara made itself physically available to hundreds of millions of potential customers. Loyalty followed market share, not the other way around.

Shein: $32 Billion Through Paid Reach

Shein took the opposite approach with the same result.

According to industry reports, Shein generated an estimated $32.5 billion in revenue in 2023, a 43% increase from the previous year. The company invests heavily in digital advertising and influencer marketing to drive customer acquisition.

The result: 261 million app downloads in 2023, 88+ million active shoppers, and 18% global fast fashion market share (surpassing even Inditex’s 17%).

Shein’s revenue went from $2.5 billion in 2019 to over $32 billion in 2023. That’s a 13x increase in four years, driven almost entirely by customer acquisition. They scaled first, and whatever loyalty exists came after.

H&M: Hundreds of Millions of Annual Transactions Through Ubiquity

H&M operates 4,000+ stores across 75+ markets. The company generates hundreds of millions of in-store and online transactions annually.

Historically, H&M grew stores by 10-15% annually, prioritizing physical availability above all else. The result: 76% brand awareness in the US, 94% in the UK.

The pattern is clear: These three companies built their positions through reach-first strategies. Zara did it through physical retail dominance. Shein did it through digital advertising at unprecedented scale. H&M did it through relentless store expansion.

None of them built a small, devoted community and grew it carefully over time. They made themselves impossible to ignore first, and loyalty emerged as a byproduct of scale.

Why “Cult Brands” Aren’t the Exception You Think

The Glossier Story You Didn’t Hear

Glossier is routinely cited as the ultimate community-driven success story. A beauty brand that grew through authentic connection and passionate fans.

But here’s the part that gets left out.

Founder Emily Weiss didn’t start from zero. She launched Glossier with significant reach infrastructure already in place. Her blog Into the Gloss had over a million monthly visitors before Glossier sold a single product. The blog featured Kim Kardashian, Karlie Kloss, and Jenna Lyons, generating massive earned media. The company raised $266 million in venture funding that enabled aggressive marketing.

That’s not a community-first brand. That’s a reach-first brand with exceptional community storytelling.

When these reach mechanisms weakened (when the blog became less culturally relevant, when Instagram’s algorithm changed, when DTC competition intensified), growth stalled. Despite genuine community passion, despite strong customer love.

The outcome? Glossier was forced to enter Sephora for broader distribution, abandoning its DTC-only positioning. After reaching a $1.8 billion valuation in 2021, reports suggest the company has struggled with profitability and scale.

Community couldn’t save them when reach declined.

Supreme’s Hidden Reach Machine

Supreme’s scarcity model is often presented as proof that you don’t need traditional marketing. Just create artificial scarcity, build hype, and let the community do the work.

Except Supreme’s scarcity model IS a reach strategy.

Every limited drop generates earned media coverage across Hypebeast, Complex, Highsnobiety, and mainstream fashion press worth millions in equivalent advertising value. The scarcity creates the story. The story creates the reach.

Celebrity endorsements (Kate Moss campaigns, Kanye West sightings, Lady Gaga appearances) provided continuous awareness to audiences far beyond streetwear enthusiasts. Collaborations with Louis Vuitton, Nike, and The North Face borrowed those partners’ massive existing reach.

That’s not a small, devoted community growing organically. That’s scale achieved through an unconventional but extremely effective reach strategy.

The Fashion Brands That Did Everything Right and Still Failed

Outdoor Voices: From $110 Million Valuation to Distressed Acquisition

Outdoor Voices built what observers called a “cult following” around laid-back fitness aesthetics and the tagline “Doing Things.” The brand reached a $110 million valuation in 2018 with backing from GV (Google Ventures), General Catalyst, and Forerunner Ventures.

The community was real. Customer satisfaction was genuine. The Instagram aesthetic was perfectly tuned to millennial fitness culture. OV had exactly the kind of engaged, passionate following that loyalty-first advocates dream about.

Then valuation crashed to $40 million by 2020. All 16 retail stores closed by March 2024. The company was acquired at a distressed price in June 2024.

Post-mortem analysis identified the core problem: like many DTC brands, Outdoor Voices overspent on customer acquisition costs and struggled to maintain consistent profitability. The company couldn’t broaden its audience beyond niche early adopters.

Outdoor Voices had loyalty. It had community. It had love. What it didn’t have was enough customers.

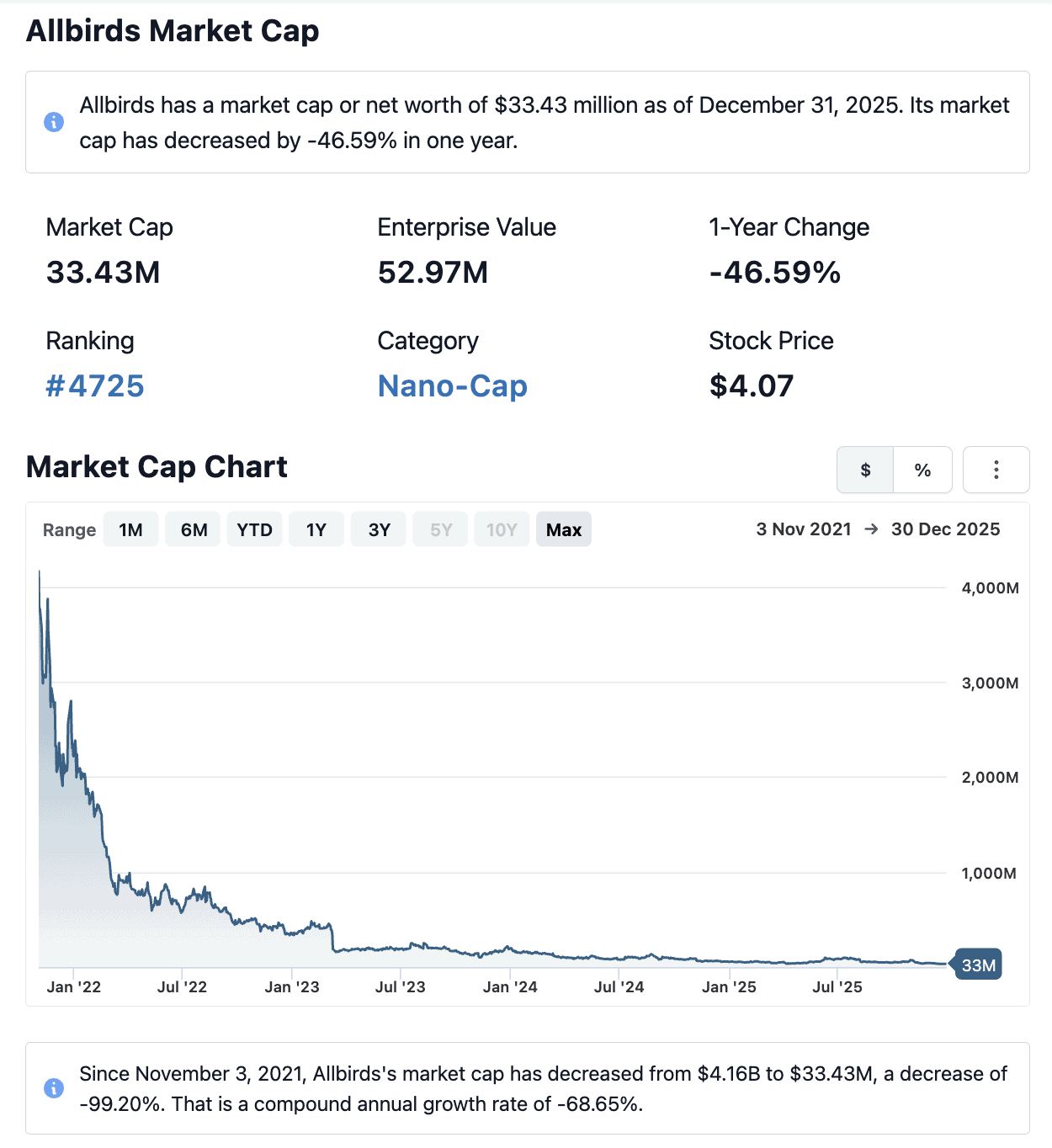

Allbirds: $4 Billion Valuation to 99% Market Cap Decline

Allbirds may be the highest-profile example of the loyalty trap.

The sustainability-focused footwear brand IPO’d in November 2021, closing its first day of trading valued at more than $4 billion. Celebrity investors included Leonardo DiCaprio. The brand had extremely high NPS scores, strong B Corp credentials, and devoted early adopters.

The “community” was passionate. The product reviews were glowing. The word-of-mouth seemed unstoppable.

Stock subsequently collapsed over 99% from peak, with market cap falling from over $4 billion to under $50 million. Revenue dropped 15% year-over-year to $254 million in 2023, and losses widened significantly.

The customer base remained too narrow, primarily reaching tech workers and urban professionals while competitors proliferated across mass-market channels.

Allbirds had loyalty within its niche. It never achieved penetration beyond that niche. And a niche, no matter how devoted, cannot sustain a multi-billion dollar valuation.

What Actually Drives Growth for Fashion Brands

The research offers a specific prescription. It comes down to two concepts:

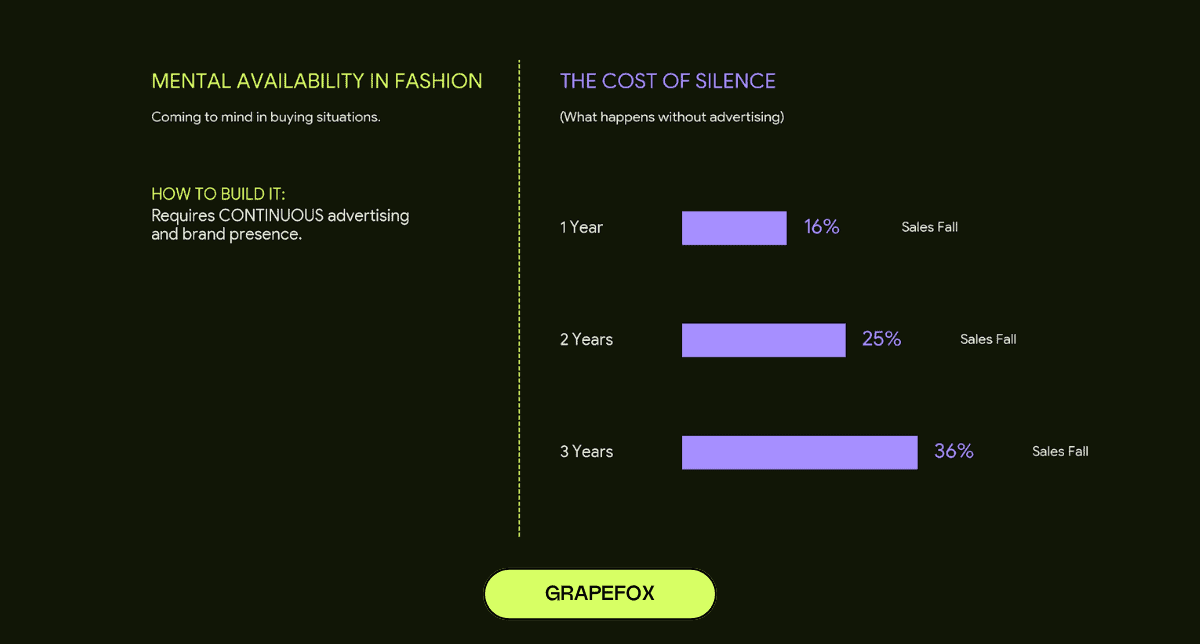

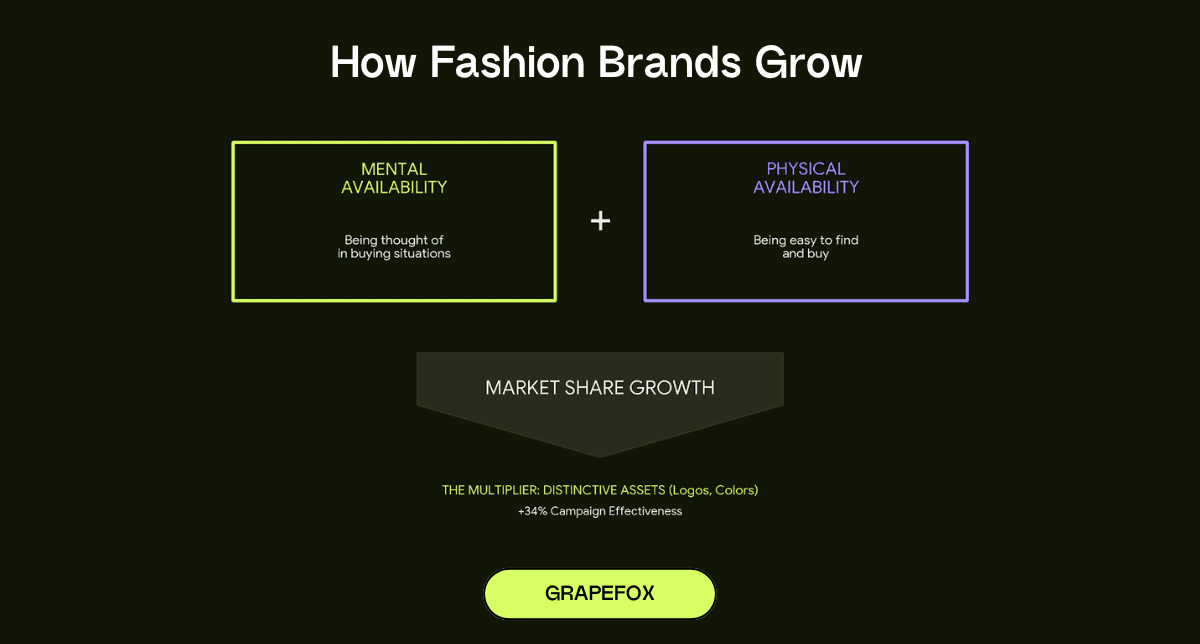

Mental Availability: Being thought of in buying situations.

Physical Availability: Being easy to buy.

That’s it. Brands grow by being mentally available (coming to mind when a consumer considers a purchase) and physically available (being accessible when they decide to buy).

Mental availability requires linking your brand to the occasions, needs, and situations that trigger purchases. “I need something to wear to a wedding.” “I want to update my wardrobe for spring.” “I’m looking for comfortable work clothes.”

Fashion brands that come to mind in more of these situations have higher mental availability. Building it requires continuous advertising and brand presence. Research shows that sales fall 16% after one year without advertising, 25% after two years, and 36% after three years.

Physical availability means distribution coverage. For digital-first fashion brands, this means marketplace presence, retail partnerships, seamless e-commerce, fast shipping, easy returns. The brands that make themselves easy to buy reach more customers.

And then there’s distinctiveness. Research shows that distinctive brand assets (logos, colors, visual elements) that trigger recognition are more valuable than claims of being “better” or “different.” Campaigns with embedded distinctive assets achieve 34%+ uplift in effectiveness.

The Tiffany blue box. The Burberry check. The Lululemon logo. These aren’t “differentiators”; they’re distinctive assets that trigger recognition.

The Path Forward for Fashion Brands

Based on the evidence, fashion brands should allocate 70-85% of marketing budget to acquisition and 15-30% to retention.

Early-stage brands with small customer bases should skew toward 80-85% acquisition. Only mature brands with hundreds of thousands of customers can shift toward higher retention emphasis, and even then, acquisition should remain the majority.

The question isn’t “How do I make my 5,000 customers more loyal?” The question is “How do I get to 50,000 customers?”

This may require sacrifices: moving from DTC to wholesale, accepting lower margins for higher volume, partnering with retailers you don’t love.

But the alternative is staying small. And small fashion brands, as Double Jeopardy shows, are penalized twice.

Stop Fighting the Wrong Battle

Small fashion brands die believing they can win on loyalty.

They die with passionate customers who loved them. They die with beautiful products and strong reviews. They die with engaged Instagram communities and glowing testimonials.

They die because not enough people knew they existed.

Big brands don’t win because they’re better at retention. They win because they’re better at reach. They’re everywhere. They’re unavoidable. They’re mentally and physically available to millions of potential customers.

And thanks to Double Jeopardy, the more market share they get, the more loyal their customers become, giving them more cash to invest in even more reach.

The cycle compounds. The rich get richer.

You cannot loyalty-program your way to significant revenue. You cannot community-build your way to market leadership. You cannot retain your way to growth.

You need more customers. Period.

Go wide before you go deep.